‘What's the difference between being a good mother and a good daughter? Practically a lot, but symbolically nothing at all.’

Motherhood, Sheila Heti (2018)

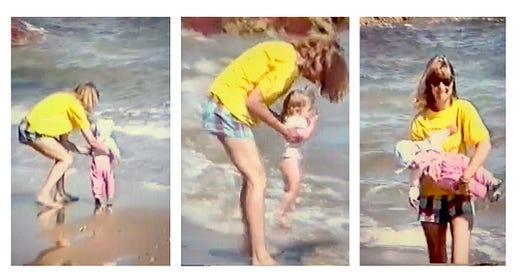

For weeks after my mother died, my father called me by her name. Sometimes he’d catch himself mid-sentence with a shake of the head. More often, he was not aware of having made an error at all.

This phase was short-lived. I never corrected him. That kind of slip is not uncommon, I’m sure, among newly widowed men. And yet over time, it took on a metonymic quality, becoming an emblem of a much larger confusion of roles and duties.

Let me give you another example. For most of my childhood, my mother was in and out of hospital. I have two sisters, five and ten years my junior. This age difference, along with our mother’s frequent hospitalisations, muddied everyone’s expectations of daughterdom—both my parents’, and my own. On countless occasions, I heard my father on the phone, talking to friends who called to ask after mum, after us. He always used precisely the same phrase: ‘Jenn just slips effortlessly into mother mode.’

I never questioned the expression, nor the adverb, until I was in my late twenties. In fact, it had to be pointed out to me. When I was a child, it did feel effortless, in a way. Muscle memory; second nature. I learned how to cook, Glad-Wrap sandwiches for lunch boxes, and keep house at a young age. But this role-playing was not effortless—even if it was years before I realised that.

When I’ve explained this to therapists or doctors or even friends, I have always rushed to disclaim: my father is a good person. He is unfailingly warm, generous, and empathetic. How could he have known it was not effortless? I never told him. I was a mostly obedient child; calm, mature, high-achieving, even-keeled. Whenever I think, write or speak about my childhood, I am at pains to point out that it is a story without villains. Everyone did the best they could.

‘Childhood is long and narrow like a coffin, and you can’t get out of it on your own.’

Childhood, Tove Ditlevsen (1967)

Everyone did the best they could. I do believe that. But the end result was the same: a slippage of identity that I was unaware of; and was, in any case, powerless to stop.

I was not Daughter—not when my mother was sick. I performed duties typically undertaken by parents; was party to conversations, and sometimes decisions, concerning my mother’s health and treatment; developed a sophisticated medical vocabulary and the ability to parse and synthesise complex information.

I was also not Mother. I felt this acutely when I was unable to soothe my sisters who missed their mum. I was both helpless and frustrated. I was trying so hard—not to replace her, but to replicate the love and comfort she provided; yet it was never enough. I was a poor facsimile. I felt it, too, when I snapped at them to get in the car, or finish their breakfasts. I wished I had more patience, more kindness, more grace. Now I look back and wonder how any of us survived.

I did not throw tantrums. I did nothing to remind anyone that I was a child. I think I even relished the confidence that adults had in me; their cool acceptance of me as—what? Not a peer, exactly, but not a child they needed to coddle, or before whom they needed to censor themselves.

It was only this year, back in February, that I came across the term ‘daughtering’, coined by researcher Dr Allison M. Alford to describe the ways in which adult daughters engage with, and care for, their parents. Daughtering is shown, she explains, ‘through the many behaviors done by a daughter in relation with her mother to fulfill the social requirements a daughter understands as ascribed or inherent to the role of adult daughter’1.

This includes, but is not limited to, practical support (driving a parent to an appointment, preparing meals, assisting with home maintenance); financial support (paying for groceries or services, or setting aside money for future use); and socio-emotional support (from visits to conflict management to putting one’s mother’s needs ahead of ones’s own).

Among the nebulous and changeable tasks ascribed to daughtering, Alford lists:

[…] the management and avoidance of conflict necessary to maintain a positive—or at least bearable—relationship; protecting herself from possible negative outcomes; considering and managing her mother’s emotions (including emotion work and emotional labor); giving respect to her mother and demanding it for her from others; deciding to fulfill or ignore obligations, whether implied or stated; management of closeness or distance within the relationship with her mother inclusive of decisions to include the mother into the daughter’s daily activities; the mental work of thinking about her mother’s well-being and future care; carrying out kin work including visits, phone calls, social media communication and assisting in the maintenance of extended family relationships; teaching and training her mother in contemporary ideas and methodologies; and eliciting mothering for herself or her family of creation2.

I am aware that The Internet has yielded a good many armchair therapists, a rash of sanctimonious dickheads weaponising the vocabulary of psychology, and a dangerous overuse—even molestation—of terms like ‘emotional labour’, ‘gaslighting’ and ‘narcissism’, all of which have perfectly legitimate and useful meanings when wielded appropriately. (As an aside, Kristin Dombek’s The Selfishness of Others: An Essay on the Fear of Narcissism is great on this topic.)

So I chafed a little against this concept of daughtering as it’s outlined above. Everything is emotional labour these days! In any normal relationship, checking in on the other person, or helping them out, is just par for the course! Sometimes a text message is just a text message!

But Alford swiftly gagged me with the invocation of ‘mothering’—a form of labour whose legitimacy I would never think to question. Which got me to thinking about how I myself have mothered. But I’m not a mother; have never been. I’m simply good at, and accustomed to, playing one.

A friend, an older man, once asked me if I ever thought about having kids. We were drunk at the pub. He’d been talking about his own adult children, and then seemed to become self-conscious that he might have been dominating the conversation (he had not). I said something like: I’ve never pictured myself as a mum, which is true. And then I added, suddenly: I used to be afraid that if I had kids, I wouldn’t be a good mother to them. I don’t feel like that anymore. But sometimes I do think that maybe I’ve mothered enough already. I surprised myself. But he accepted what I had said, understood it, and I was grateful.

Alford (quoting a fellow researcher) notes that mothers are ‘semantically overburdened’—that is, that ‘mothering’ is often used as a catch-all term to describe virtually any and all caregiving work, from domestic labour to time management, and from managing relationships to managing others’ emotions. I am not a mother, but I have been doing mother-work since I was a child; before, in fact, it was possible for me to biologically reproduce. I began to think about this as lowercase-M motherhood, which I have performed in caring for my parents, sisters, partners, and friends since early childhood.

There is something interesting here, to do with language and its insufficiency.

‘If a mother was Sacrifice personified, then a daughter was Guilt, with no possibility of redress.’

The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera (1984)

In her research, Dr Alford interviewed a number of adult daughters whose mothers were self-reliant, cognitively intact, and living independently. In the absence of more precise terminology, daughters often use the word ‘mothering’ to describe the work they undertook for their mothers:

Throughout the interviews, using the term mothering, daughters were communicatively constructing their role performance as a daughter, describing their active daughtering and participation in the mother-daughter dyadic relationships even when precise words were unavailable. Stories about mothering one’s mother described nurturing mothers and mothers’ acceptance of that nurturance3.

This is to say: daughtering is outside language.

Daughters’ responses revealed a lack of precise language for describing their experiences, resulting in the use of borrowed language to describe their behaviors in the adult daughter role.

Beyond the narrow academic application of research like Alford’s, the roles played by and the work undertaken by daughters is either ignored or uncomfortably subsumed by the word ‘mothering’.

All of this is semantic, yes. Who gives a fuck, when my father’s freezer is a mess and I need to pick up his prescriptions from the pharmacy, whether I’m mothering or daughtering. (The other interesting thing is: the research on ‘daughtering’ seems to focus exclusively on the mother-daughter dyad. And don’t get me wrong; it’s a fascinating relationship—but surely the role of daughtering can also be said to be performed for (to?) fathers, as well? A topic for another missive.)

But I do find comfort in the idea that there’s a word for what I, and daughters like me, are doing. I’m doing more of it than either of my money-earning jobs. So much of the work is invisible, even to its beneficiaries. Naming it makes it feel real.

Thanks for being here. Take care.

Alford, Allison M. (2019) cited in 2021's ‘Doing daughtering: an exploration of adult daughters’ constructions of role portrayals in relation to mothers’, Communication Quarterly, 69:3, 215-237, DOI: 10.1080/01463373.2021.1920442, p217

Ibid.

Ibid.

To say this speaks volumes to me is a gross understatement. As always I adore your writing, but the content floored me. I'm at the other end, mothering a decrepit impossible mother who is a cross between a recalcitrant toddler and sulky teenager. Thank you for writing.

PS - many years ago, accosted you at the All Nations pub in Richmond and fan-girled. Still makes me cringe.

thank you for writing this <3